A conversation with Jan-Hendrik Boelens, former chief engineer at Airbus Helicopters, CTO at Volocopter and Quantum Systems, and now Co-Founder and CEO of Alpine Eagle, a next-generation defense startup redefining how the skies are secured.

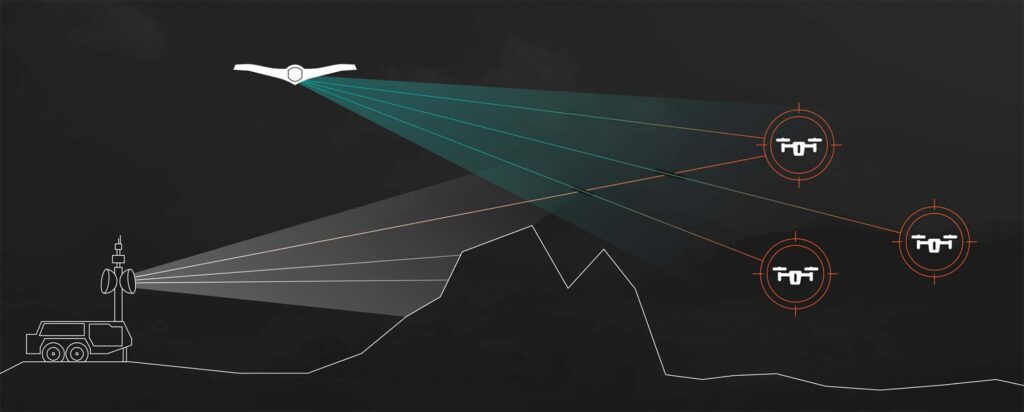

The company builds fully aerial counter-drone systems that keep the entire kill chain—sensing, command, and effectors—in the sky: From hunting low-flying First Person View (FPV) drones—which are easy to miss for ground radars—to intercepting high-altitude surveillance drones. Alpine Eagle’s distributed, mobile platforms give operators a bird’s-eye view and allow for a faster, more flexible way to respond.

Recently, Alpine Eagle has raised €10.25m in seed funding, led by IQ Capital with participation from HTGF, Expeditions Fund, Sentris Capital, General Catalyst, and HCVC. We discussed the pivotal moments that shaped the company, their approach to defense procurement, the fundraising landscape for defense tech and dual-use in Europe, and the best strategy to grow as a European defense-tech startup.

What’s Alpine Eagle Mission?

We’re building a fundamentally different counter-unmanned aircraft system (C-UAS).

Our approach is entirely aerial: from sensors to effectors, the whole kill chain operates in the air. That’s our core differentiation: You get a bird’s-eye view, mobility, and fewer blind spots than ground-based systems.

Counter-UAS system: Systems used to detect, track, identify, and neutralize hostile drones. These systems combine sensors—radar, RF detectors, and EO/IR cameras—with mitigation tools like jamming, spoofing, or interceptors to safeguard airspace, infrastructure, and personnel.

Is Countering Low-Flying Drones, Like Fiber-Optic FPVs, Your Main Use Case?

That’s where we started two years ago—FPV drones flying low and fast.

From the air, you can see what ground radars can’t, and you can distribute mobile sensor platforms over a wide area. But once we engaged with European MoDs, law enforcement, and the Ukrainian Armed Forces, we saw broader use cases.

What we’ve observed from the conflict in Ukraine is the emergence of a whole new dimension of offensive counter-UAS operations.

Instead of waiting for enemy drones to approach friendly forces, there’s now a proactive approach—actively hunting down enemy drones before they ever get close, particularly (Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance) ISR drones. These missions can be conducted right near the front lines or even deep behind them, using aerial counter-UAS platforms.

In my view, this represents a major shift—from traditional point defense to a broader concept of air dominance. We’re seeing this transformation unfold daily in Ukraine, and at Alpine Eagle, I believe we’re helping build a key part of that evolving capability.

Looking Back, What Were the Top Three Pivotal Moments in Alpine Eagle’s History?

First, finding the right co-founder early on is crucial. You only have an idea, so the people around you bring it to life. For me, that was Timo Breuer.

Second, securing a launch customer before the pre-seed runway ended. Securing a next raise without revenue is a tough sell for a startup.

Third, our first trials in Ukraine. Moving from the safety of testing systems with Western MoDs to a real operational environment changed everything. European proximity to Ukraine helped us learn fast.

Startups Move Fast; Defense Procurement Doesn’t. How Do You Reconcile That?

By decoupling development from tenders.

If you try to act like a new prime contractor, you get trapped in bespoke specs and one-off builds. That kills speed and scale. Plus, often, customers don’t even know what they’ll need yet. By the time a specification is written, three years have passed, and it’s already obsolete.

We design and ship commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) products to our own spec, which lets us move at our own pace. When a tender lands, we adapt as needed, but building according to your roadmap first is the only way to maintain velocity.

You Hit Seven-Figure Revenue Within 12 Months Since Starting the Company. What Unlocked That?

A ruthless focus on customers from day zero.

From Volocopter, I learned not to spend years building without validating market demand and willingness to pay. We developed some great products, but we lacked customers to validate whether the market was ready for them.

The key lesson I took from that experience is: don’t spend 10 years developing a product without knowing if there’s a real market for it—and how much, if anything, customers are actually willing to pay.

We embraced Lean Startup principles: form hypotheses, test them quickly with real buyers, and iterate. While my co-founder led the product development, I was fully dedicated to landing the first contract.

Fundraising in Defense Tech Can Be Tricky. How Did You Approach It?

Initially, we were uncertain whether European VCs would be willing to fund a startup focused on single-use solutions rather than the conventional dual-use strategy.

So we started with a sensor-focused, non-lethal value proposition to stay well within common LP guardrails. We figured that if we went out there saying we’d be shooting down drones, not many VCs in Europe would be ready for that.

Two things happened. First, our assumptions were positively disproven—several European VCs were more open than expected. Second, the market evolved; interpretations of LP boundaries became more permissive, though there are still red lines around offensive weapons.

Counter-UAS is inherently defensive, and that helped. We also built a cap table spanning key European markets—the UK, Germany, Poland, Estonia, and France—to support multi-country scale.

What Do You Think About the Current Limitations Placed by Some Investors?

I think that three years into the war in Ukraine, we should already be further along. We shouldn’t still be having debates about whether offensive weapons are permissible or whether explosives are acceptable.

It’s fair to debate whether offensive or defensive weapon systems make sense as venture-backable cases from an economic perspective—that’s a valid conversation. But drawing artificial ethical lines in the sand about what is or isn’t backable simply because it involves kinetic capabilities feels outdated and misaligned with the current geopolitical reality.

How Do You Recruit Top-Tier Talent for a Defense Startup?

Start with purpose. Two or three years ago, many engineers in places like Germany wouldn’t consider defense. Ukraine and the broader geopolitical shift changed that.

I think one important factor is that we’re building purely defensive systems—technologies designed to protect against drones.

The threat is visible and widely recognized, whether it’s in Ukraine, Mexico, Colombia, or even drones flying over critical infrastructure and airbases here in Europe. These incidents are regularly covered in the media, so people understand the seriousness of the problem. That visibility makes them more inclined to support—or want to work for —a company like ours.

And finally, it really comes down to two key factors:

Brand recognition—if people know who you are, understand what you do, and perceive you as one of the more successful, high-growth startups, that makes a big difference.

Talent attracts talent—when you have exceptional people on your team, it naturally draws in others of the same caliber. On the other hand, a mediocre team can deter top-tier candidates from joining.

Defense Hasn’t Seen Many Exits Yet. How Do You Think About Alpine Eagle’s Path?

I think globally, there’s been a significant traffic jam when it comes to exits. Many large unicorns and even bigger startups have been waiting a long time for the right opportunity to exit. This isn’t a challenge unique to defense—it seems to be a broader issue affecting the market as a whole.

Specifically in defense, I’d say that for most startups—especially in Europe—it’s simply too early. If you look at their life cycles, very few are at a stage where an exit would make sense.

Quantum Systems, for example, is probably one of the more mature players, and they’ve been around for about 10 years. By contrast, companies like ours or others in the ecosystem have only been around three or four years, which is generally too soon for an exit. In the European defense market, timing is the main issue: most startups aren’t yet far enough along in their life cycle.

There are two main exit scenarios. One is an IPO—I think we’re starting to see that this can actually be a viable path with Anduril contemplating it. The other is an M&A transaction by a defense prime. If you look at the stock performance of major defense primes, there appears to be ample opportunity for them to reinvest capital into acquiring innovative startups at a later stage.

If You Could Start Over, What Would You Do Differently?

I’d hire a bigger team earlier. We could have moved faster with a few more key people in place.

I’d also structure the company so fundraising and operations run in parallel. Fundraising consumes more time than you expect; if half the company is fundraising, operations stall.

Except for these changes, no regrets. I think moving abroad early on was one of our best decisions. Over the next 12 to 24 months, I expect some defense startups will get stuck in their home markets, relying solely on their national Ministry of Defense as a customer. Without expanding beyond that, they might make some limited sales—perhaps to Ukraine—but that’s not a scalable path.

These companies risk becoming small-to-medium enterprises rather than high-growth startups, which will make fundraising increasingly difficult. They may survive on local revenue, but without scale, they’ll either be acquired or quietly disappear.

The few startups that will truly succeed are those that manage to break into multiple international markets early. In Europe, especially, with its fragmented landscape of national defense customers, international reach is critical.

U.S. startups have the advantage of a massive domestic market, but in most other regions, going global is essential. I believe we made the right strategic moves early on to position ourselves in exactly that direction.

Do You Expect Europe to Harmonize Defense Procurement Anytime Soon?

I’d love to be surprised, but I don’t see rapid harmonization.

The entire European Union has historically carved out defense as a separate issue—it was never truly integrated into the EU framework. Defense remains an extremely sensitive and politically charged topic, and today, most European governments are operating in a “my country first” mindset.

Given the strength of national interests, the political climate is unlikely to support rapid progress toward a unified European defense market.

There’s too much at stake: public money is being spent, and politicians are under pressure to ensure it supports local companies and creates local jobs. That’s why we can’t afford to wait for the market to become a level playing field.

The momentum needs to come from the other side—companies themselves must ensure they are capable of operating internationally from day 1.

Written by Paolo Trecate